A couple of days ago I read an article in Wired about the Centre for Health and Human Performance (CHHP) and their newest work with high intensity interval training. CHHP is a London based clinic and research centre that has been working with some of the world’s top athletes. They use asymmetric loading of muscles varying between concentric action (shortening of muscles to bear effort typical for the “classical” fitness) and eccentric action (strengthening + lengthening) in order to decrease body fat while increasing muscle mass.

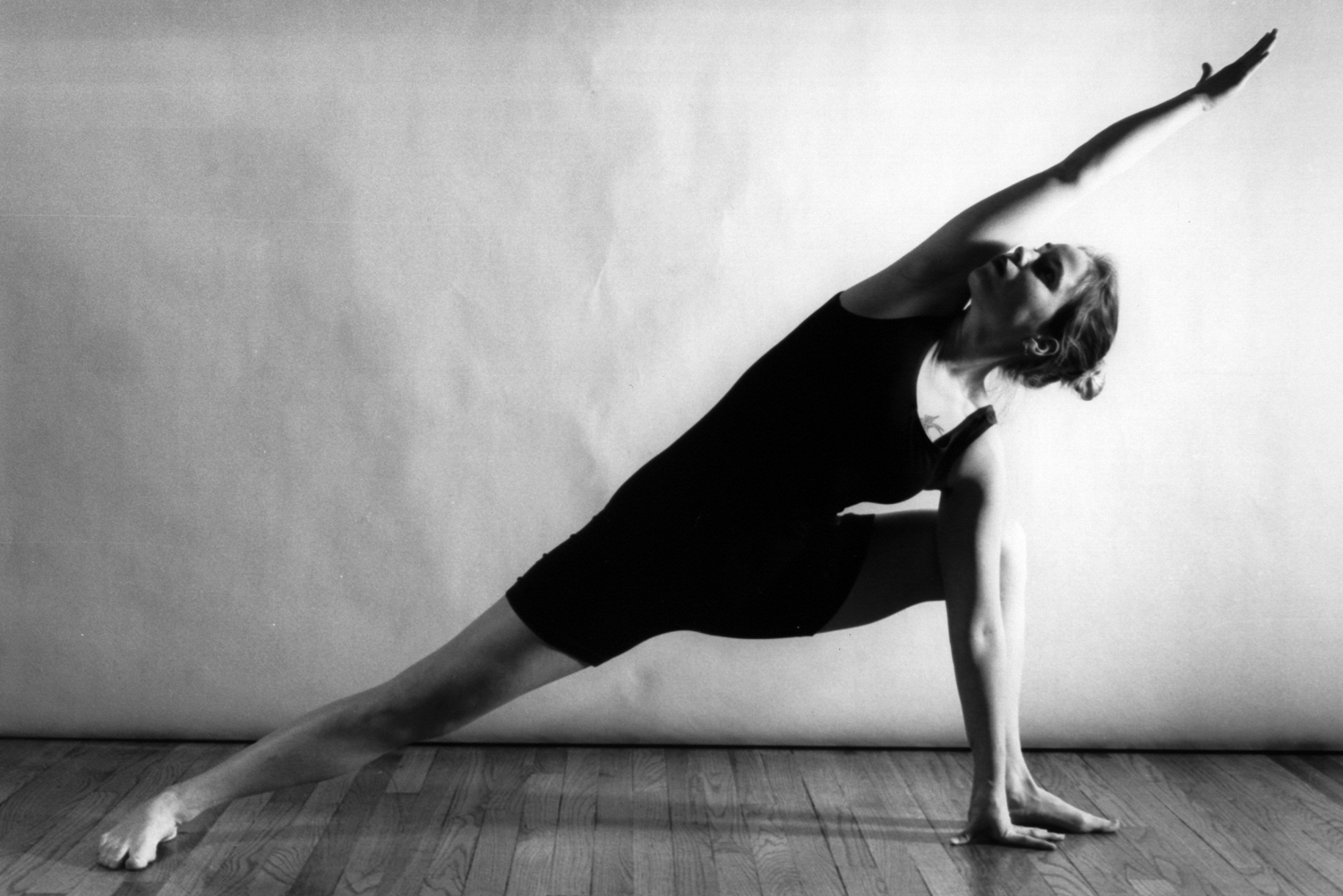

I find it interesting that newer research in fitness puts more accent on eccentric loading of muscles, typical for yoga. This is the action of keeping a sustained contraction of a muscle while “relaxing into the effort” of keeping the pose, so the muscle can steadily lengthen at the same time. And this is the very thing that makes (the physical part of) yoga so special and so much more than simply stretching or getting a good workout.

Doug Keller beautifully explains the concept of eccentric muscle work in yoga in his groundbreaking set of books Yoga As Therapy. Looking into the structure of muscles, they each consist of a bundle of fibers, encapsulated within fascial wraps. The fibers themselves are made of long protein cords organised in rows. Such structure allows the muscles to shorten without actually having to shorten themselves. It’s just the fibers gliding into each other, similarly to two old-school shaving brushes. If you push the brushes into each other the bristles won’t shorten or contract but just slide into one another, merging into one. This way we can understand how the muscle doesn’t actually loose it’s flexibility as it contracts, it can still lengthen and this is what happens during the eccentric contraction.

Intrestingly, this is a type of contraction that is common to different types of skeletal muscles that inherently work differently. According to one of the most widely accepted categorisations of muscles set fort by Vladimir Janda in 1970-es, the skeletal muscles are either: postural - that maintain the contraction / resistance to hold the bones in place, or phasic - that contract when needed in order to move the bones.

These two don’t just work differently, they are fuelled by a different substance too. The postural muslcles are fueled by oxygen and as such are slow to fatigue and can work continuously without us even thinking about them. This is how we are supposed to maintain out posture against the gravity without getting tired.

On the other hand, the phasic muscles are powered by blood sugar or glucose and need constant energy input to be able to work. They are generally the ones who do the “heavy lifting” and more powerful than the postural ones, but fatigue much quicker.

The postural and phasic muscles work together and balance each other’s work. As we move the phasic muscles get consciously activated to get us moving while the postural muscles support their action by providing resistance that keeps the body together and maintains our posture against gravity.

The phasic muscles tend to weaken through lack of use or overuse, due to bad postural habits for example - funnily enough, undoing some of our hard work of developing and strengthening we did as babies to be able to learn to walk. On the contrary, postural muscles have tendency to shorten and tighten over time, more or less depending on how we use the body. And these two phenomenons come in pairs for specific muscles - for example, weak abdominals come in pair with tight psoas. For this reason Keller is writing a lot about the need to address muscles in pairs. In order to strengthen weak muscles we need to release the tight postural muscles that balance them.

Eccentric muscle action allows us to do both at the same time - strengthening while lengthening and both phasic and postural muscles are able to work eccentrically, just with a little bit of practice. And eventually we can release the muscles lengthwise as we activate them, even the postural ones, which usually work without us worrying much about them.

Learning to consciously activate the postural muscles in yoga together with the phasic ones, allowing them to release and lengthen as we contract and lengthen the phasic muscles, the pose grows almost effortless. For example, with a bit of practice you can keep your hands up in the air as the spine lengthens, using almost no effort of the arms as the postural muscles along the spine keep the body in the pose and being able to “relax upwards”. And this is how yoga practice creates the feeling of length and spaciousness in the body.