More time I spend learning about the body more I wonder: do we really need “core strengthening” to make us stronger? We might be trying to solve a wrong problem, blaming everything on “the core” as some powerful source of strength inside the body that we need to train and strengthen in isolation from everything else.

It’s interesting how the approach to abdominal exercises has been changing in last couple of decades — from the military-style crunches in 1980-es with the lower back pushed into the floor, to keeping the small curve in the lower back in 1990-es. And then in late 1990-es the whole concept of “core” came up and everyone got obsessed with transversus abdominis (TrA) and pulling the navel in like pressing a magic button of stability and strength.

A couple of weeks ago I came upon an intriguing article by Prof. Eyal Lederman that added some more oil to the fire of my doubt pointing to quite a bit of research that could shake the grounds of the widely-accepted idea of “core stability” training and its efficiency.

The idea of “core” and its training is a reductionist fantasy based on arbitrary assumptions—Lederman says.

The concept of “core stability” emerged out of a research showing a change in onset timing of the muscles of the torso in patients with back injuries and chronic back pain. But then, combined with the Pilates idea of strong abdominals as a base of strength, it stretched to involve a couple of arbitrary assumptions. First, that there is a separate group of “core muscles” that works independently from the rest of the body and that we can train in isolation. Second, that training the “core” can help cure back pain and prevent injury.

Lederman points at a couple of different studies conducted on pregnant and postpartum women that show that there is not necessarily a link between weak abdominals and back pain. He challenges the key role of TrA in stabilising the torso and questions the widely-spread idea that training TrA can help with back pain or reduce the recurrence of back pain.

But what I found the most interesting, was deconstructing the myth of muscle timing training, which is the base of “core stability”. We are talking about one fiftieth of a second difference in muscle activation in case of people with back injuries comparing to healthy subjects. These timings are well beyond the patient’s conscious control and the clinical capabilities of the therapist to test or alter — he says. Even if we could effectively re-train muscle timings, that would mean interfering with a complex mechanism that our bodies use to protect us from further injury.

You could go around the timing problem by activating TrA all the time. But this way you use a force that is often more than what you need to efficiently perform a task, unnecessarily compressing the lumbar spine. Also tensing of the abdominal muscles increases intra-abdominal pressure which in some cases (e.g pelvic girdle pain) can cause further damage to pelvic ligaments.

Trying to override the body’s defence mechanism developed through thousands of years of evolution by pulling the navel in is not only energy inefficient, but can even lead to injury.

Another thing which really resonated with me, was examining the “core stability” approach from the aspect of similarity principle in learning of motor skills. “We can’t learn to play the piano by practicing the banjo” — Lederman says. If you learn to activate TrA while lying on your back, there is no guarantee that this would transfer to control and physical adaptation during standing, sitting, bending, lifting, running.

Which basically means, the only way to strengthen the body to be able to respond to various positions is to use it in all of these. Or in other words — to MOVE.

Which made me think, our hunter-gatherer ancestors never went to a gym and probably never ever thought of doing any core strengthening and still had enough core strength to survive in wilderness hunting their lunch. But the thing is, they moved — all day, every day, more in summer, less in winter, but at least a couple of miles every day. They climbed trees, carried their children, sat on the ground to prepare their food and eat. And none of them ever even heard of core stability.

Our modern weak core epidemic, sort of, is a response to the way we live and use our bodies day to day — driving everywhere, spending most time sitting on couches and comfortable chairs. There is rarely any need to use your strength, unless maybe sometimes carrying a suitcase up the stairs when the lift is out of order or occasionally moving a piece of furniture. And then you throw your back out.

We need to think out of “the core” to fix the core — Katy Bowman, biomechanicist and founder of Nutritious Movement™ says. Can 3–5 hours in the gym offset the rest of the week spent sitting, pretty much in one position every day from nine to five?

The same as what we eat shapes us, the way we move over time shapes us too. Not just exercise, but every movement and lack there of counts.

Our bodies have adapted to very limited use and repetitive positioning of the joints throughout the day. As some of our hardly used joints stiffen and whole areas of the body clump together, unable to move independently, the joints that still DO move have to bear all of the strain for the ones that don’t. And this is the body we bring into the gym and “challenge”, pretty much asking for injury.

It’s often not strength that is the problem, but mobility.

‘You’ll often find that “hard moves” you thought you weren’t strong enough to do were actually hard because your body wasn’t mobile enough to capitalise on the geometry that makes them doable.’ — Bowman says. Through using the body more and in more ways, we can restore mobility in the stiff areas and allow muscles to do their job in stabilising the body as we move.

Your “core” works in respond to every movement of the body, and the lack of movement. No matter what kind of a “core strengthening” programme you might use, if you don’t move that much or that well your “core” will continue being weak.

We need to bring movement back into the way we live, bit by bit. Not only in the gym. Not only to “challenge” ourselves after a whole day or even weeks and months of not moving. Exercises are useful, but they just can’t work in isolation. It’s what we do all day that counts.

Bowman makes a parallel between movement and nutrition in which exercises are an equivalent of vitamins — useful as a supplement only, but not able to replace eating well altogether.

A healthy movement diet looks something like this:

- Walking, walking , walking

- Squatting and sitting on the floor

- Lifting and carrying

- Hanging and climbing

So the same as we make effort to eat our 5 servings of fruits and veggies per day, we need to make sure to squeeze in at least a bit of each of these types of movements in our day as the main source of our movement nutrients.

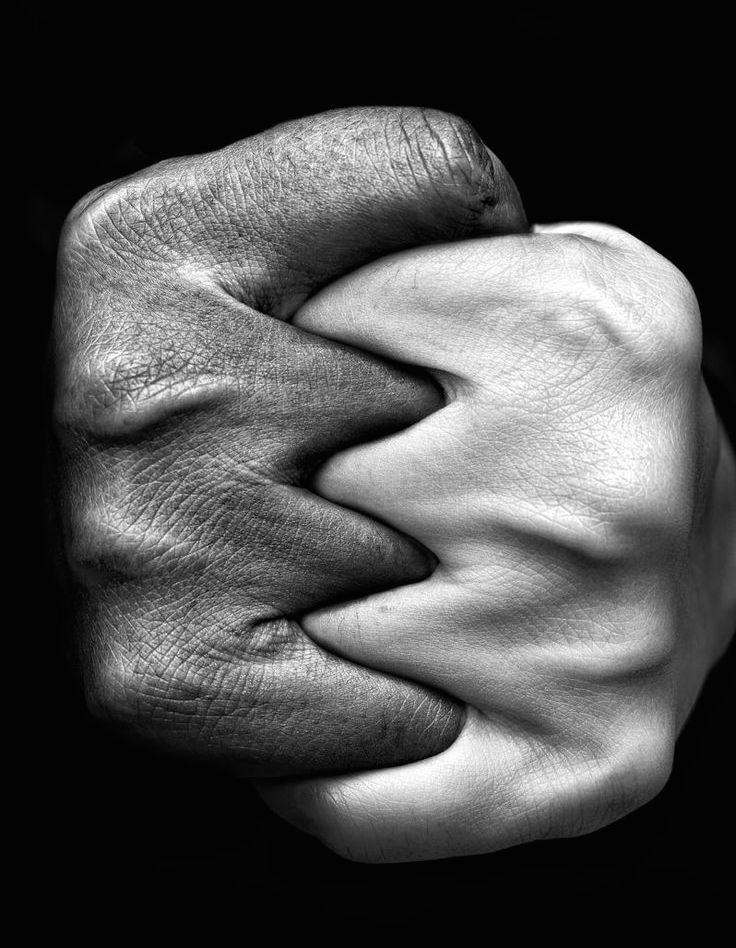

The body stabilises itself in response to movement. It’s all about proprioception — sensing and responding to the environment as we move. Our feet and hands behave as sensory organs giving us information through a level of joint distortion. And even looking deeper into the body — our muscles not just execute the movement but also react to the sensory input of the environment, tensing and releasing when needed.

There is no need to “engage your core” to stabilise the spine. If you need to make an effort to activate your “core” squeezing and forcing, it probably means that either your muscles are not sensing the load or the load is more than your current strength.

And this is basically the same view I found in work of dance educator Hubert Godard — there is no need to keep the tension in the centre but allow the body to respond freely to movement, gliding fluidly between the earth and the sky.

So my point is: maybe it’s time to stop worrying about “the core” and make space for more movement in our lives.

Walk, squat, use your arms more and in more ways, climb a tree if you can. No exercise programme can strengthen a body which is not being used otherwise. It’s only a healthy variety of movement that can keep your joints supple and your muscles at optimal length to be able to generate force.

And release the belly — instead of keeping it pulled in all the time, leaving space for the body to stabilise itself as and when needed. A relaxed and responsive body is a strong body.

This article was also published on Medium

Reference list:

Eyal Lederman — The Myth of Core Stability, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies Volume 14, Issue 1, January 2010, p. 84–98

Katy Bowman, MA — Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement, Propriometrics Press, September 25th 2014

Radebold, A., et al. — Muscle response pattern to sudden trunk loading in healthy individuals and in patients with chronic low back pain, Spine, 2000, 25(8): p. 947–54.

Helewa, A., et al. — Does strengthening the abdominal muscles prevent low back pain — a randomized controlled trial, J Rheumatol, 1999. 26(8): p. 1808–15

Katy Bowman, MA — Diastasis Recti : The Whole Body Solution to Abdominal Weakness and Separation, Propriometrics Press, January 2016

Hubert Godard — Reading The Body in Dance http://www.somatics.de/Godard/ReadingBodyInDance.pdf